Note to readers: Biological Expositions is a series of blog-posts each of which is equivalent in content to a book chapter. If bio-bullets are likened to a starter, blog-posts could be seen as a light lunch and Biological Expositions as a three course meal. We look forward to your comments on this series.

Is a woman’s peniform the sole organ of erotic dedication – or an essential feminine multitasker?

Robin: Welcome, Mammalian Clitoris, our first organ to be interviewed here in the Biological Expositions series of blog-posts at the Bio-edge. Exposing your real nature may startle any listeners who assume that – much like nipples on a male chest – you’re just a vestige from the opposite sex.

Mammalian Clitoris: Thanks, Robin and the Honey Badger, it’s good to get air time and I’m likely to surprise both sexes. Who knew, for example, that in many species of mammals – from bears to bats – I’m large enough to have my own skeleton?

Robin: Skeleton? Meaning you contain articulating bones, additional to the pubic bone?

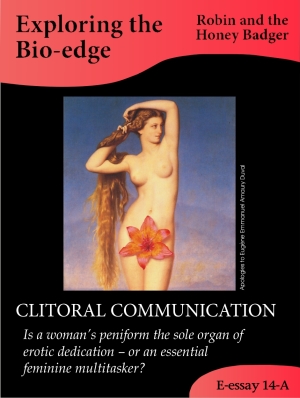

Mammalian Clitoris: Just one rod-like bone actually, which reinforces the clitoris. But forked in certain primates and up to 40 centimetres long in elephants.

The Honey Badger: That does deserve to be better-known.

Mammalian Clitoris: As does the fact that in elephants neither the proboscis nor the proboscis-like penis has any bony reinforcement whereas I have tens of centimetres of bone. And equally surprising is that the muscles attached to this clitoral bone allow female elephants to twitch me in ways beyond the dreams of even the best-hung human male.

Robin: But you’re always smaller than the penis, surely?

Mammalian Clitoris: Not necessarily. Has any zoologist actually surveyed the full spectrum of mammals to establish which is more prominent in each species, the clitoris or the flaccid or retracted penis?

The Honey Badger: But in which mammals could you possibly rival the size of the phallus even in its quiescent state?

Mammalian Clitoris: Well, several species of primates, true moles and carnivores have a clitoris that resembles the penis. And in spider monkeys and their relatives the pendulous clitoris looks longer than the flaccid penis of the same species.

Robin: Spider monkeys and their relatives already show an evolutionary stretch by possessing tails so prehensile that there are fingerprints at the tail tip. From your description it sounds as if their projecting clitoris is also finger-like in a way.

The Honey Badger: But why on Earth would these monkeys be particularly endowed with an organ of heightened sexual pleasure?

Mammalian Clitoris: To clarify your question why would you think that I’m a sex organ in these monkeys?

Robin: Well surely the point of the clitoris, whatever its size or prominence, is to stimulate the female during sex, either in foreplay or during copulation itself?

Mammalian Clitoris: If that’s a common assumption, you may be misunderstanding my basic nature.

Robin: Are you saying that educated women are misguided in celebrating you as the only organ known to be devoted solely to erotic sensation?

Mammalian Clitoris: I doubt that a broader knowledge of zoology would’ve led to the view that my function is to heighten sexual pleasure. Women today may be falling for a pseudo-scientific interpretation of my role.

Robin: But surely humans are more highly evolved than other primates and an intensely erotic clitoris is part of the sophisticated sexual biology of the species with the best-developed nervous system of any animal?

Mammalian Clitoris: That’s a view that might appeal to politically correct humans, particularly emancipated women, but it’s wishful nonetheless.

The Honey Badger: Isn’t it true, then, that the human clitoris has among the most nerve-endings of any part of human anatomy?

Mammalian Clitoris: Possibly, but the sensitivity and pleasure of a rubbed clitoris can promote behaviours that go far beyond sex. And my capacity for orgasm doesn’t necessarily mean that my functions are only consummated orgasmically.

The Honey Badger: Well, obviously the penis doubles as a urinary spout, but you don’t. So what else could your purpose be besides sex?

Mammalian Clitoris: You say ‘obviously’ but that’s another partial misconception – if you look beyond humans. In certain mammals I do indeed form a urinary spout, making me an organ of micturition like the penis.

The Honey Badger: Really? In which mammals is the clitoris peniform to the degree of containing the urethra as well?

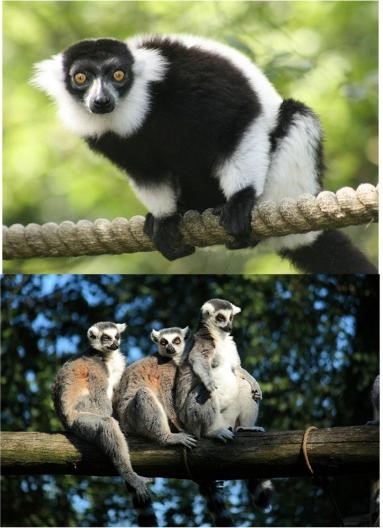

Mammalian Clitoris: Several and various mammals have a clitoris that doubles as an organ of micturition. Primitive primates such as galagos and lemurs and true moles, for example. And, as a carnivore, you may be surprised to know that at least one member of your own order has a micturatory clitoris.

Robin: But even if some aberrant mammals get rid of urine through the clitoris, why would they want a clitoris in the first place, if not for sex?

Mammalian Clitoris: The answer might be obvious to listeners but for the blindness of shame. Scent production. In all mammals including humans, I’m mainly devoted to producing, collecting, processing and emitting personal scents.

The Honey Badger: With all those nerve endings?

Mammalian Clitoris: Well, it’s pleasant to rub me on objects, hands or other individuals, whether this results in orgasm or not. Haven’t you seen that look of bliss on a cat’s face when it rubs the scent-gland on its jaw against objects as part of its scent-marking behaviour?

Robin: I hadn’t made the connection.

Mammalian Clitoris: Perhaps think of most of the pleasure of the clitoris as a para-sexual reward. Nature’s way of ensuring that animals don’t neglect the important chore of scent production.

Robin: So you’re inscentive incarnate – with an extra ‘s’?

Mammalian Clitoris (smiling): If you want to be clever.

Robin: I suspect that many listeners will cling to the view that the clitoris is purely sexual if the definition of sex is broad enough to include homosexuality and masturbation.

Mammalian Clitoris: If so, I ask: which woman hasn’t wondered at the perversity of female anatomy? She can’t urinate – even by squatting – without wetting the clitoris and even the pubic hair. The labia minora tend to hold any residual urine and the labia majora tend to channel residues towards the clitoris. Do listeners believe that’s just bad anatomical design?

The Honey Badger: Point taken, the anatomical coincidence is a bit too easy to take for granted. The sexual and waste-discharging orifices are, as you say, placed so close together in all mammals that a function involving urine can hardly be ruled out for any clitoris.

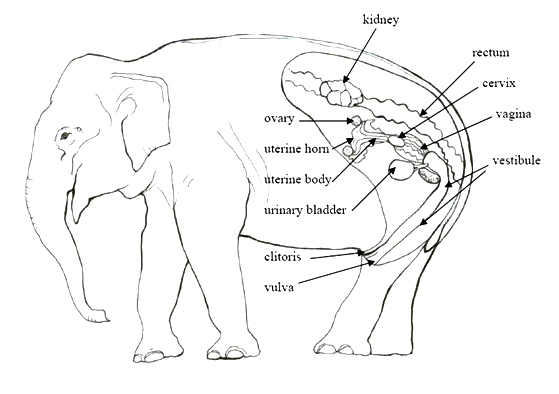

Mammalian Clitoris: Well, please consider that the design may not be accidental but a case of multiple use, nuanced in various ways in the various mammals. For example, in some primates the urethral opening is located, as in humans, in the vulval vestibule between the clitoris and the vagina. But in other primates, the urethral opening is located as far forward as the tip of the clitoris, as in galagos, or as far back as inside the vagina itself, as in the bonobo.

The Honey Badger: As someone who can smell an object with the kind of depth and involvement a human gets out of watching a whole video clip, I follow the importance of scent production. But what’s the source of clitoral scent in most mammals?

Mammalian Clitoris: Sources plural. Firstly, epithelial products, of the prepuce similar to those of the penis. Secondly, various glands on or near the clitoris, depending on the types of mammals. But much of my olfactory value comes indirectly, by channeling products from, thirdly, the urinary tract and fourthly, the vagina.

The Honey Badger: I see the anatomical complications. In addition to what you produce yourself, you’re a staging post for urine and other products that are processed on you and then emitted, partly by being rubbed on to objects.

Mammalian Clitoris: Well, let’s first talk about urine. It wouldn’t be too stretched to generalize that I’m a ‘drip-tip’ for urine in many species even though I contain the urethral opening in only a few species. In most mammals, urine anoints me one way or another. And, perhaps surprisingly to listeners if not to you, Honey Badger: urine is far more than just a waste product. It contains pheromones and other olfactory substances that can affect most mammals consciously or subconsciously.

Robin: And the sources you mentioned besides urine?

Mammalian Clitoris: For example, there are secretions from the female equivalent of the prostate, which can actually be ejaculated from the urethra by some women.

Robin: As a bird I find that difficult to imagine.

The Honey Badger: I have no experience of it either, although to put off enemies I can squirt stronger stuff from other glands around my anus. Which non-human mammals would be capable of female ejaculation and in which species could such discharge occur independent of copulation?

Mammalian Clitoris: Unfortunately, biologists have tended to shy away from asking themselves such questions; little research has been done.

Robin: And which sources besides the female equivalent of prostatic ejaculate?

Mammalian Clitoris: Several other secretions, including from inside the vagina, potentially find their way to the clitoris because of the configuration of the genitalia in humans and other mammals. And then the combination of excretions and secretions is nuanced by subsequent bacterial action.

Robin: So clitoral scent is a real anatomical and chemical formulation that goes beyond the merely glandular?

Mammalian Clitoris: Yes, think of me as a communicator with a rich syntax.

The Honey Badger: Well, I certainly find that various urinogenital products tell me a lot about the health and status of my friends and acquaintances, whether the messages are sexual or not. And now that you mention it I suppose the clitoris is involved as much as any other body part.

Mammalian Clitoris (smiling): Thanks for the acknowledgement.

The Honey Badger: But do humans really use this kind of olfactory sophistication? In my experience, when it comes to smell, they’re rather oblivious yet easily offended. No offence to listeners.

Mammalian Clitoris: Fair to assume that natural personal scents affect humans of both sexes more than they care to admit. Perhaps some of it is subliminal.

Robin: Do clitoral scents affect only mature males?

Mammalian Clitoris: No, females and juveniles as well. For example, women tend to synchronise their menstrual cycles within the group, and this may be achieved partly through pheromones emitted from the clitoris and its vicinity. And in the spotted hyena– the species with the most penis-like clitoris of all – clitoral scents seem to be directed mainly at other females and have to do with social status and rank in the hierarchy rather than sexuality per se.

Robin: So how much does genital anatomy vary among primate species?

Mammalian Clitoris: The complexity is enough to bewilder most biologists, and the human clitoris is neither representative of primates as a whole nor shown to be any kind of evolutionary pinnacle.

The Honey Badger: Primates generally differ from other mammals in smelling less and seeing and thinking more. But I take it that they retain enough of a sense of smell to maintain the biological importance of scent production by the clitoris?

Mammalian Clitoris: Well, my degree of development does depend to some extent on the visual system of the primate in question. Relatively poor eyesight is usually associated with a keen sense of smell and, hypothetically, a prominent clitoris relative to other primates.

The Honey Badger: Which primates have poor eyesight by mammalian standards? African and Asian monkeys certainly have much sharper eyes than mine.

Mammalian Clitoris: I’m talking mainly about variation in colour vision. African and Asian monkeys see in full colour and display the clitoris, vulva, perineum and associated seasonal swellings with bright hues. But nocturnal and primitive primates, and also certain anthropoids, have relatively poor discrimination of colours. For example, certain South American monkeys can’t distinguish red from green. So those primates remain relatively reliant on smell and their prominent clitorises reflect this.

Robin: Does that help to explain spider monkeys, which we’ve already discussed?

Mammalian Clitoris: Yes, they may be like miniature apes in some ways but they don’t have the excellent colour vision of apes. Perhaps that’s relevant to the fact that spider monkeys have a long, deeply grooved clitoris that channels some urine from the vulval vestibule.

The Honey Badger: And we’ve seen that lorisoids such as galagos go the extra step of using the clitoris to micturate in the same way as the penis. Are you implying that these large-eyed nocturnal primates have even poorer colour vision than in South American monkeys?

Mammalian Clitoris: Yes, because if woken by day, galagos and other lorisoids can’t even see yellow as dogs do, making them effectively colour-blind. And both female and male galagos routinely use their peniform organs – the penis in the male and the similar-looking clitoris in the female – to place urine on to their palms. They then wipe the urine on to their soles to leave their personal scent wherever they climb and jump.

The Honey Badger: You mentioned that true moles might have a similar clitoral structure to galagos, with the urethral opening at the tip. Isn’t that convergence odd, given that galagos have exceptionally large eyes and true moles have exceptionally small eyes?

Mammalian Clitoris: Yes, in true moles the penises and clitorises are so similar that it’s difficult to distinguish females from males. But neither galagos nor moles may find it convenient to communicate socially by visual signals, given their normal habits.

Robin: So how do true moles use their micturatory clitorises?

Mammalian Clitoris: Well, the function is poorly known, but once again probably involves complex communication by scent. True moles differ from other moles in maintaining permanent systems of tunnels that are patrolled regularly by one individual at a time, suggesting a particular reliance on scent-marking.

The Honey Badger: Coming back to primates to finish our train of thought: so those monkey and ape species that see all the colours of the rainbow produce relatively little scent, including from the clitoris?

Mammalian Clitoris: That’s the general idea although even primates with full colour vision do use the clitoris for scent production. African and Asian anthropoids rely partly on brightly-coloured swellings of the vulva during oestrus. And in the bonobo the chemical clues outside oestrus tend to be tasted rather than smelt, leading to routine presentation of the clitoris for tasting by one female to another.

Honey Badger: I’m sure we could devote a whole blog-post to the biology of the bonobo. But you mentioned my order of carnivores earlier?

Mammalian Clitoris: That’s too good to miss. The fossa of Madagascar is peculiar in developing a particularly large clitoris at the most unexpected time of its life: when it’s still sexually immature. At birth, the clitoris is not particularly prominent, and the same is true again in the adult female. But in the intermediate years when the female has left its mother but not yet settled down to defend its own territory, that’s when it develops its clitoris in a remarkable way.

Robin: What’s remarkable apart from the size?

Mammalian Clitoris: It’s spiny, a bit like the penis of its father. It also has a long clitoral bone, which, together with the spines and most of the rest of the clitoris, is reabsorbed once the female reaches sexual maturity.

The Honey Badger: So that the clitoris of the breeding female fossa once again reverts to something unremarkable for a member of the carnivore order?

Mammalian Clitoris: True.

Robin: Let me get this straight. You’re saying that the fossa has a large clitoris only during the time in its life when it’s not yet ready for sex? And that this transient clitoris has bony and spiny reinforcements to boot?

Mammalian Clitoris: Believe it or not. And the sexually immature female uses its clitoris for scent production in ways that cease when she becomes adult.

Robin: For social rather than sexual reasons?

Mammalian Clitoris: Well, nobody fully understands the reasons, but they probably have to do with the fact that the fossa grows more slowly to full size than do most other carnivores, and so the female has a prolonged juvenile period and delayed sexual maturity. If so the main need of the ‘tween’ – for want of a better term for this stage of life – is to be tolerated as a trespasser in the territories of adult females and to be able to eke out a living in the interstices until a territory-holder dies and a vacancy becomes available.

The Honey Badger: So you’re saying the sexually immature female fossa uses olfactory messages to pacify its would-be evictors as a way of buying time?

Mammalian Clitoris: Perhaps. The ‘tween’ may be using her masculinised clitoris to pretend to be male from an olfactory perspective. Her masculine scents would hypothetically elicit the same tolerance from adult females that allows males to overlap their territories with impunity.

Robin: But how would that explain the spiny glans of the clitoris?

Mammalian Clitoris: Maybe the spines serve to hold residues of urine for bacterial processing. The urethral opening in the fossa is at the base of the clitoris, which in itself is unremarkable. But what is significant about this opening is that the clitoris and the vagina are all held within a purse-like vulva until extruded by muscular contraction that turns the entire complex inside out for purposes of copulation or, presumably, scent-marking. Then there would be a mixture of stale urine and certain secretions on the spiny part of the clitoris, which can be used for scent-marking objects in the environment.

The Honey Badger: Oh I see, you’re suggesting that micturition normally occurs with the vulva pursed, so that urine soaks the hidden clitoris, which can later be extruded to produce scent as a convincing facsimile of male scent?

Mammalian Clitoris: Yes. The spiny penis of the fossa presumably retains residues of urine, so perhaps the clitoris would need similar spines to maintain olfactory credibility as a gender-faker?

Robin: Why is the fossa so significant?

Mammalian Clitoris: Because it shows that the clitoris is not mainly sexual. This can be taken as indicative of mammals in general, unless someone can come up with a counter-example – namely a mammal in which the clitoris only develops after sexual maturity.

Robin: Any other reason?

Mammalian Clitoris: And also because it suggests that other para-sexual features, such as the supposedly vestigial nipples in male mammals, would be reabsorbed if they were truly functionless.

The Honey Badger: The case of the fossa is so remarkable that I’m wondering why we haven’t heard of it before.

Mammalian Clitoris: Well, the anatomy was described years ago. But biologists are scared stiff of speculation, and besides it’s hard to see the world as the fossa does.

Robin: Why is that, again?

Mammalian Clitoris: Partly because scientific language is based on human experience. We haven’t had a term to describe the extended period, as the female fossa grows up, when it’s already been weaned and has left its mother’s side, but hasn’t yet reached sexual maturity. ‘Juvenile’ is too vague. This period can be described as ‘post-dispersal pre-sexual maturity’ but that’s awkward and still ambiguous, because the young fossa hasn’t necessarily dispersed far. That’s why I suggested ‘tween’.

Robin: Okay, semantics aside, I understand that the important point is that the female fossa spends several years independent of its parents but not yet sexually mature, and it’s during that period – not before or after – that it possesses a large, complex clitoris.

Mammalian Clitoris: That’s a fair summary, which should feed thought for anyone who sees me as mainly or purely a sex organ.

The Honey Badger: If you’re instead for scent production, we might predict that even in the human species you function before sexual maturity.

Mammalian Clitoris: And that would be true. Any parent knows that I’m already producing smegma in girls only five years old, when they haven’t even developed a sense of personal privacy yet, let alone any sexual awareness.

The Honey Badger: And how does this relate to that other carnivore, the spotted hyena – a species that scares even me a bit stiff?

Mammalian Clitoris: The clitoris of the spotted hyena is the closest known replica of the penis in any female mammal, although it has yet to be proven capable of female ejaculation. It’s as long as an erect human penis; it’s tipped by a glans with miniature spines as in the penis of the same species; and it’s the opening for both sexual intercourse and micturition.

Robin: And the peniform clitoris is well-developed at all ages in the female spotted hyena?

Mammalian Clitoris: Yes, from birth to death. This also means that the spotted hyena actually gives birth through what appears to be a penis.

The Honey Badger: How is such parturition possible in your experience?

Mammalian Clitoris: Birth is particularly risky for the mother in the spotted hyena, because each newborn, weighing about 1.5 kilograms, must travel right through me. Listeners can stretch their minds to a human penis somehow passing an object half as heavy as a human baby. Sometimes I tear in this process, although the spotted hyena is a tough species and I usually heal later.

Robin: So here’s an odd thought. The peniform clitoris of the female spotted hyena, already present in the foetus, is actually born through the peniform clitoris of its mother?

Mammalian Clitoris: That’s never occurred to me before.

The Honey Badger: So what is the function of this ultra-stretchy clitoral replica of the penis in the female spotted hyena?

Mammalian Clitoris: Once again, mainly social communication. The female cocks her hind leg, but not to squirt urine on olfactory signposts as done by male dogs. Instead, she presents the erect – or should I just say distended – clitoris to other females for sniffing in routine greeting.

The Honey Badger: Do you experience this as a kind of sexual interaction?

Mammalian Clitoris: Not really. I’m certainly stimulated in the process, but females don’t necessarily greet males in this way and courtship doesn’t particularly involve the clitoris. What’s more, the spotted hyena indulges in less foreplay than humans do, and the male mounts the female hyena from behind as in other mammals – albeit with much more patience than in most.

Robin: So what are the differences between the fossa and the spotted hyena, given that both seem to have perverse development of the clitoris?

Mammalian Clitoris: Well, more differences than similarities, really. I’m not particularly developed in the juvenile female spotted hyena whereas I am in the juvenile female fossa.

Robin: As we’ve already gathered … And?

Mammalian Clitoris: A basic difference is that the clitoris contains a urogenital canal in the spotted hyena but not in the fossa – which instead resembles most other mammals in that the urethra and vagina open separately. But a complication is that the clitoris is permanently external in the spotted hyena but usually hidden inside a vulval purse in the fossa.

The Honey Badger: We’ve got to wind up but would you like to mention any other groups of mammals that we haven’t already covered?

Mammalian Clitoris: Well, the contrast between pigs and rodents might make an interesting study. Pigs have an internal clitoris whereas various rodents have a clitoris so external that it could be called perched.

Robin: Intriguing.

Mammalian Clitoris: Female rodents of various kinds produce scent with a urinogenital projection beyond the clitoris itself. For example, rats have a female urethral papilla superficially resembling a furry penis, with the urethral opening at the tip. However, the clitoris is really located halfway along its length, and on the anterior side, away from the vagina. By contrast, in pigs the whole clitoris is so far inside the urogenital tract that it’s invisible from the outside.

The Honey Badger: And the functional implications?

Mammalian Clitoris: Well, my role in scent production might remain despite these variations in anatomy. In the case of pigs I’m fully stimulated during copulation whereas in rodents I’m not even touched by the penis during copulation. But regardless of my role in sex, I can produce scents – which emerge from the vulva in the case of pigs and remain extraneous to the vulva in rodents.

Robin: I wonder if any listener still has reason to think that you’re a purely sexual organ in any mammal. We look forward to seeing their comments.

Mammalian Clitoris: I challenge biologists to find out which mammals experience female orgasm and which don’t – and if scent-marking in itself leads to orgasm in the absence of copulation in any species.

Robin: We’ve really stripped the emotional and political fabrics in which people have invested you. Could you please let listeners know what you feel is a biologically – if not politically – correct approach to you?

Mammalian Clitoris: Well, men and women alike, by all means indulge me with imagination. But please don’t close yourselves to the possibility that I play to the same tune of multi-use that’s so pervasive throughout biology. Although an engineer might design each tool for one purpose, nature knows the ultimate economy. And please don’t flip culturally from one extreme to another, first amputating me for producing unwelcome odours, then idealising me as fit for a goddess.

Robin: A basic lesson here seems to be that, although a violin may be designed just for sweet music, living organs necessarily combine functions – some of which may be overlooked even when they’re right under our noses.

The Honey Badger: A good note on which to finish. On behalf of listeners we thank you, Mammalian Clitoris. We look forward to meeting again when we interview the next organ in the Biological Exposition series here at the Bio-edge.

***

All text and images appearing in this blog are subject to copyright, except those images explicitly stated to be in the public domain. You are not free to use any photographs, for any purpose, without receiving written permission from the copyright holder.