Amputating[1] the clitoris is, by any standards, an abuse of the human body. As in the case of a hand amputated, some functions have been lost. But which functions, exactly?

The answer ‘sexual pleasure’ is too simplistic. This is because a politically correct eye on sexual pleasure can only be maintained if it is accompanied by an equally politic blind nose to the other obvious function of the clitoris – a particularly scented part of the body.

Societies that routinely amputate the clitoris have lost respect for the biological nature of our species. But using pseudo-science to elevate the clitoris to a fanciful status, as a specialised sex organ claimed by women in triumph over men, is also ignorant albeit at a higher intellectual level. For it should be fairly obvious, whether anthropocentrically or from the comparative anatomy of mammals, that the clitoris makes little sense as an exclusive organ of sexual pleasure.

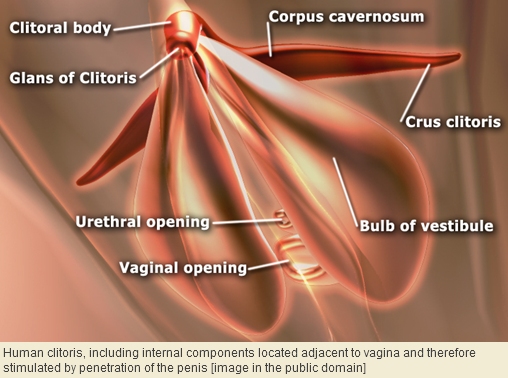

The anatomical position of the human clitoris is indifferent for sexual pleasure, because it’s not as close as it could be to the vagina. And much about the external anatomy of the female urinogenital system makes more sense in emitting personal olfactory messages. The lack of any urethral spout[2] for clean micturition[3]; a clitoral prepuce to produce smegma; labia minora to retain and mix urine and secretions from both the vagina and the periurethral glands, and to drain these towards the clitoris; and pubic hair to retain and emit scent.

When a woman’s clitoris is amputated, a level of sexual function is denied because this organ is by far the most sensitive part of our urinogenital system. However, what is also denied is a level of emission of personal scent.

But our emotional ambivalence about personal scent, now shunned as odour, has dumbed us down scientifically. An almost religious regime of removing clitoral odour by means of modern hygiene may not, after all, be so different from the medieval mentality of removing the problem with a rusty blade. While there’s no comparison in terms of violence, the denial of personal expression of femininity – whether in scent-production or in orgasm – reflects an ignorance of biology. Worse, a disinterest in biology.

Although the vagina is by definition the entrance[4] and exit[5] for the reproductive system, there are wide options for the anatomical placement of the clitoris (the focus of pleasure) and the urethral opening (the point of micturition) relative to the vagina. The diversity of designs in mammals far exceeds the imagination of most biologists. It’s only by waking up and smelling the coffee of these permutations that a realistic perspective can be obtained.

Both the clitoral prepuce and the urethral opening are, in their own ways, sources of scent. The prepuce secretes smegma, for little discernible reason other than communication by scent. Fresh urine contains its own chemical clues, such as pheromones, and its staling by bacteria adds new layers of olfactory information, for example about immunity. Given that the head of the clitoris and the point of micturition are both sources of what becomes complex olfactory information, let’s briefly survey the axes of variation in their placement – relative to the vagina – in various mammals.

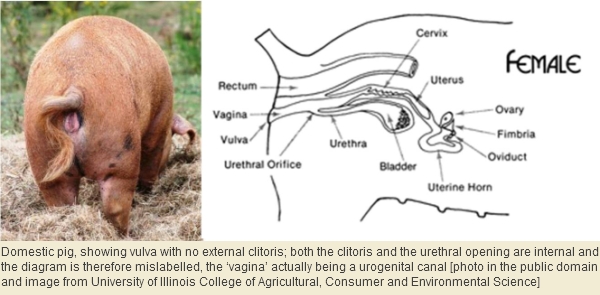

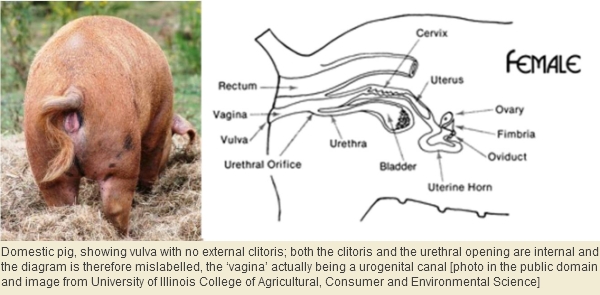

In pigs[6] both the clitoris and the urethra are hidden inside, some five centimetres behind the vulva. Strictly speaking, the vagina of the pig does not reach its vulva at all, this final five centimetres being instead a urogenital canal, which is by definition shared by reproduction and micturition. If there are mammals in which the clitoris is placed consistent with sexual pleasure, pigs are the ones, because the insertion and thrusting of the penis must necessarily stimulate the clitoris fully. However, the anatomy even here is ambivalent because the urine is potentially capable of washing clitoral[7] and other internal secretions to the vulva, where the mixed products are then exposed to the discerning nose of pig society.

At the opposite extreme on the same axes, we have primitive primates such as the ring-tailed lemur[8]. Here, both the clitoris and the urethral opening are so separate from the vagina that their sensory role during copulation is questionable, stimulation instead being achieved by spines on the penis. The female ring-tailed lemur has what appears to be her own (spineless) penis, complete with an enclosed urethra; i.e. she micturates from her clitoris just as most male mammals do from their penises. Once again, the olfactory value of clitoral secretions and urine are confused (with possibly synergy), but lemurs are instructive because they show that neither the glans[9] of the clitoris nor the point of micturition are likely to be in contact with the male during vaginal penetration. We can think of the external urinogenital system of the female ring-tailed lemur as effectively consisting of one part – the vagina – specialised for sex and birth and another part – the tubular clitoris – specialised for micturition and the production and emission of scent[10].

We’re only talking about lemurs, but this is relevant to the human condition. Lemurs, like us, are primates. And were women’s genitalia similar, it would be a stretch indeed to suggest that the clitoris is an organ exclusively devoted to sexual pleasure, or different from the penis in the potential production and emission of scent.

Although the necessary study has yet to be done, most mammals can theoretically be arranged somewhere along the dual axes of relative distance from the glans of the clitoris to the vaginal opening, and relative distance from the urethral opening to the vaginal opening. The human species has a moderate position within this rage of variation. Even if we accept that humans have a uniquely developed capacity for orgasm, this need not distinguish us categorically from other mammals in the function of our clitoris. After all, orgasms often come from masturbation; it is pleasant to rub the clitoris whether orgasmically or not; and intermittent contact, often with the hands, can potentially help to emit the scent. Present company excepted, of course.

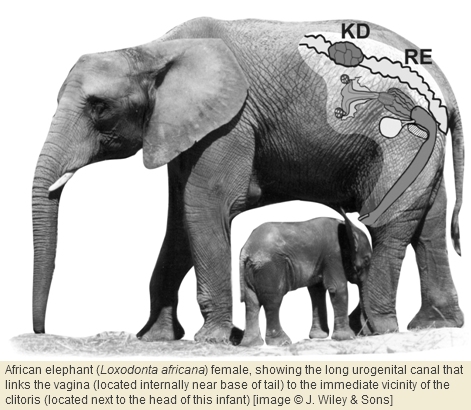

Although the anatomy of certain mammals widely separates the clitoris or urethra from the vagina, it’s noteworthy that in all cases the three are connected by a urogenital canal or groove[11] that potentially retains their combined olfactory value. Elephants epitomise this, because both the vagina and the urethra end deep inside the body, near the base of the tail. Nearly an extra metre of urogenital canal is needed to connect them to the clitoris, which is located about as remotely from the anus as can be imagined. This means that the large, muscular clitoris of elephants can mix and emit scents derived from its own secretions, urine, and whatever other substances are produced by glands and linings along the entire urinogenital tract and urogenital canal.

Anthropoid primates can’t rival elephants in the degree of separation of the clitoris from the vagina or the muscularity of the clitoris, but they do their best to show the error of looking at the human species in anthropocentric isolation. The examples are less extreme but show the same principle. For example, spider monkeys[12] have a clitoris as long as, or longer than, the corresponding penis, and there is a deep groove connecting its tip to the urethra – which opens between clitoris and vagina. The combination of a vulval vestibule and a clitoral groove means that vaginal secretions, other urinogenital secretions, and urine can reach the ‘drip-tip’ of the clitoris, a pendulous organ routinely leaving scent on branches. The clitoris of spider monkeys is non-erectile, and remote enough from the vagina to make its involvement in copulation tenuous. Yet its involvement in emission of scent is clear and the combination of several different sources of scent makes biological sense.

What these examples show is that, although clitoral anatomy varies greatly among mammals, the common denominator is scent rather than sex. We are starting to see that smegma is, in both sexes, a urinogenital secretion as opposed to a purely genital secretion. The logic here is that the clitoris, unlike the vagina, is not a sex organ in the strict sense.

The thrust of our lateral thinking can be presented as follows. The common denominator between clitoris and penis, in mammals generally, is production and emission of scent. In all cases, the scents of these peniform organs include glandular secretions as well as urinary components. What differs between the sexes is that the male, additionally, uses the peniform organ for intromission and insemination. This turns on its head the current, pseudo-scientific interpretation of the clitoris. For although not even Macho would claim that his micturatory spout is exclusively sexual, the penis emerges overall as more sexual – across the spectrum of mammals and possibly including humans – than the clitoris. In some mammals the clitoris seems virtually irrelevant for copulation, whereas the same cannot be said of the penis in any species – the multiplicity of functions of all peniform organs notwithstanding.

So where does this leave that outrageous example of evolution of a female peniform organ, the spotted hyena[13]?

The spotted hyena is essentially similar to elephants in that the vagina and urethra are hidden deep inside, and what connects them to the exterior is a urogenital canal. As in elephants, copulation is impossible without the full cooperation of the female and rape is out of the question. Yes, the female spotted hyena has what appears to be a penis and yes, it copulates, passes urine, and gives birth through this same clitoris. Unlike lemurs, this clitoris contains not the urethra but a urogenital canal. And unlike elephants, the urogenital canal opens not adjacent to the clitoris but near its tip.

But, once the mind comes to terms with such anatomical confusion, two overlooked points emerge. Both are relevant to the human species regardless of how reluctant we may be to compare ourselves with hyenas or to embrace the implication that their odours are somehow our scents.

Firstly, in the spotted hyena as in all mammals, the most frequent function of the clitoris is to produce, collect[14] and emit olfactory messages. It is erected not sexually but socially, usually in interaction with other female individuals. Secondly, it’s hard to imagine a clitoris less likely to produce sexual pleasure than this, the most peniform of all mammalian clitorises. For the only means of copulation is for the clitoris to become so flaccid and introverted that it emulates a vaginal opening – something that it certainly is not. And the glans of both penis and clitoris in this species has a rough surface which would seem to demand extraordinary lubrication to prevent friction. If we assume that erection, vascular engorgement and smoothness are the keys to clitoral consummation, the spotted hyena is the wrong man for the job.

We don’t yet know whether the female spotted hyena experiences sex as pleasure or pain. But ironically this species, by bringing the clitoris into what is perhaps the most intimate contact with the penis in any mammal, gives the lie to the belief that the ultimate embodiment of sexual pleasure is the mammalian clitoris. The spotted hyena has sex despite the clitoris rather than because of it – unless by some poorly understood neural rewiring the clitoris, flaccid to the point of introversion, comes full circle back into an exquisite sensitivity to penetration. It’s known, for example, that ovulation in cats[15] and various other mammals is induced by the insult to the vagina by barbs on the penis. So we can speculate that similarly harsh stimulation is the closest thing to orgasm experienced by the spotted hyena during copulation. And it seems a safe bet that, when the female spotted hyena does enjoy its clitoris, this is usually – if not only – during olfactory intercourse with other females, foreplay to nothing sexier than social status.

***

All text and images appearing in this blog are subject to copyright, except those images explicitly stated to be in the public domain. You are not free to use any photographs, for any purpose, without receiving written permission from the copyright holder.

What good is a clitoris?

1 i.e. clitoridectomy

2 A urethral papilla, which occurs in various mammals but not primates, would help to discharge urine with minimal wetting of the skin and hair.

3 the act of passing urine (urination is a function of the kidneys, not the urethra)

4 i.e. for sperm

5 i.e. for newborns and menstrual discharge

6 Sus

7 We assume that the pig clitoris produces smegma despite its internal location.

8 Lemur catta

9 i.e. the extremely sensitive head of the clitoris

10 And even the vulva itself plays a role in emission of scent, with large labial glands (almost resembling a scrotum) occurring close to, and on each side of, the vaginal opening.

11 i.e. vulval vestibule, whether external of internal

12 Ateles

13 Crocuta crocuta

14 as in other mammals, combining scents of clitoral, vaginal, urinary and other origin

15 Felidae