Although much richer in bird species, South America cannot match Australia’s large, brainy passerines.

With a relatively well-watered, reliable environment, it’s not surprising that South America supports many bird species, each specialized in its own way. By contrast, the unreliability of Australia’s resources, particularly rainfall, is likely to limit specialisation in birds while at the same time favouring braininess on the island continent.

This is because intelligence – even in birds – can be an adaptation to unpredictability of living conditions.

The use of tools by birds can, for example, boost versatility in foraging. And a good capacity for memory – as revealed by vocal mimicry – may be crucial for surviving drought, fire and flood. This logic would explain why Australia has particularly brainy passerines despite having relatively few species of small suboscines[1]. In this blog-post we delve into the details of this comparison.

But first a geographical perspective.

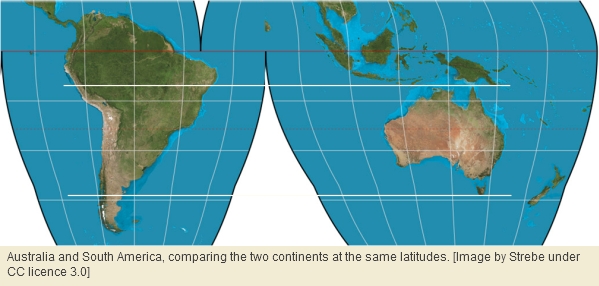

The torso-like segment of South America that corresponds in latitudes to Australia happens to have a similar area to the whole of the island continent: about 7.7 million square kilometres. Both Lima in Peru and Salvador in Brazil line up in latitude to the northern tip of Cape York Peninsula, while Chiloe Island in Chile corresponds to southern Tasmania. This rather neatly frames our intercontinental comparison notwithstanding the fact that many species of Amazonian and Andean birds are ruled out of the study area because equatorial South America lies beyond the northernmost latitude of Australia.

However, even that subset of the total passerine avifauna of South America which corresponds latitudinally to Australia greatly outnumbers the total list for the island continent. To put numbers to this: in equivalent areas at the same latitudes, South America supports nearly 3.5-fold more species of passerines than the approximately 306 species supported by Australia. Most of these South American species are small suboscines associated with rainforest – a radiation represented in Australia only by pittas[2].

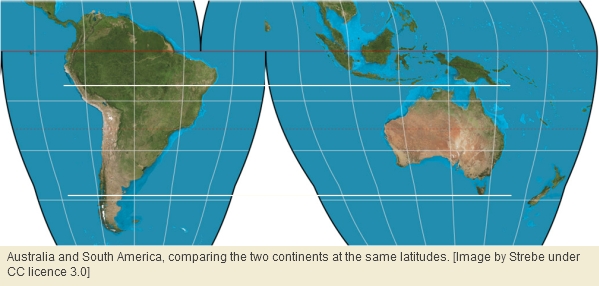

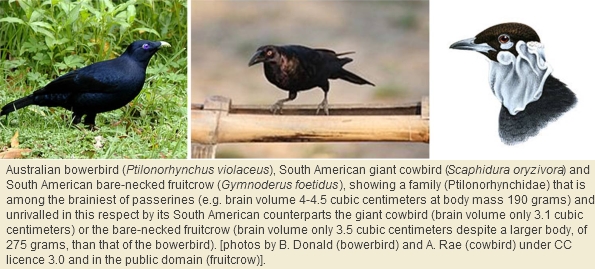

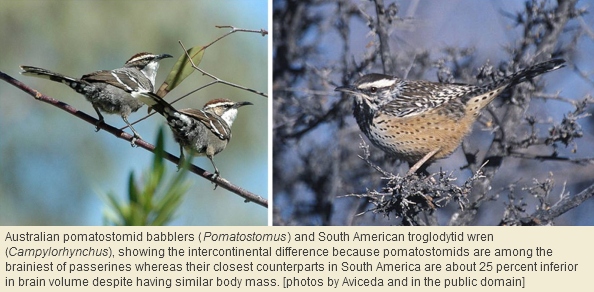

The part of this which has particularly caught our attention here at the Bio-edge is an apparent intercontinental difference in passerine intelligence. At least six genera of passerines in Australia[3] have been recorded using tools[4], whereas we know of no such records among South American birds[5]. And although many passerines – including relatives of the South American oropendolas[6] and cowbirds[7] – are capable of mimicry, certain Australian species such as lyrebirds[8], bowerbirds[9] and the Australian magpie[10] seem to be particularly accomplished mimics. What’s more, no South American bird[11] seems to match lyrebirds or bowerbirds in the complexity and versatility of their learned behaviours in song and courtship.

If we narrow our focus to the large passerines, in which female body length exceeds 38 centimetres, another anomaly emerges. There are thirteen species in four families of these large passerines in Australia. By contrast, South America at the same latitudes has only three species, and these collectively cover only a third of the area because they avoid the relatively dry or cold parts of South America.

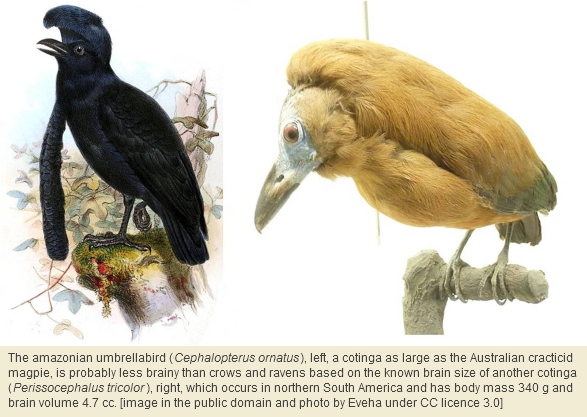

Relative to total numbers of birds within our compared areas, Australia consequently is nearly fifteen-fold richer in large passerine species than South America. Apart from the difference in numbers, there’s also a shortfall in body size, with none of the South American large passerines achieving the female body length of any Australian species of raven[12], crow[13], lyrebird or currawong[14] or the white-winged chough[15]. It’s also worth emphasising that ravens and crows are absent throughout South America and that lyrebirds have no counterparts on that continent.

The superb lyrebird[16], with a brain size exceeding even those of ravens or crows in Australia (10.7 cubic centimetres compared to 9.8 cubic centimetres in the Australian raven[17]), is the largest passerine in Australia and the second-largest on Earth. By comparison, the largest passerine in South America at Australian latitudes is the olive oropendola[18] (female 42 centimetres), which is related to finches rather than corvids[19] and doesn’t rival any crow or raven in brain size. An oropendola of this size is likely to have a brain size of not quite 6 cubic centimeters[20]. Furthermore, the Australian corvids are impressively brainy relative to South America’s largest oropendula. To be precise: the little crow[21] of Australia has similar body mass (379 grams) to the oropendola but with a brain volume of 6.4 cubic centimetres, and the little raven[22] has an even greater brain volume of 8.5 cubic centimetres despite its smaller body mass (300 grams).

Australians tend to take for granted the ubiquity of crows and ravens. However, the native presence of these birds throughout the island continent is noteworthy given that they’re among the most intelligent of all animals. How many readers knew, for example, that the 8.5 cubic centimetres of brain in the little raven living around Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney is nearly 3.5-fold greater than the brain volume of a brown rat[23] of similar body mass? And sure enough, certain species of crows or ravens are the most adept of all birds at making, using and storing tools.

South America also has corvids, but they hardly compare with the brainy members of this family in Australia. The only corvids in South America are many species of jays, which are not as large and – if similar to jays elsewhere – not as brainy as crows and ravens relative to body size. Bowerbirds and jays are comparable in body size, but bowerbirds seem superior in brain size. Furthermore, none of the South American jays[24]extends south of Buenos Aires or enters semi-desert, whereas crow-like passerines in Australia, in the form of currawongs, the Australian cracticid magpie and the white-winged chough, extend far south of latitudinally similar Sydney and seem to rival jays in intelligence. So it seems that all relatively large passerines in South America fall short of crows and ravens in braininess.

So why are the two austral continents at odds in terms of bird brains? As noted in the opening paragraph, the differences in both body sizes and relative brain sizes may be explained by the unreliability of resources in Australia. The island continent is smaller and drier than South America, and more subject to an erratic cycle of drought, fire and flood because of the El Nino Southern Oscillation, from which South America is buffered by the Andes and the Atlantic. And, although Brazil is nutrient-poor, no part of South America can rival the intensity of fires associated with Eucalyptus and the flammable hummock grass[25] of Australia which result in considerable losses of nutrients.

Australia’s drought and nutrient-poverty is consequently more extreme than South America’s. The large avian brains in Australia have evolved, we suggest, to find and secure the few resources available that provide sufficient nutrition – even after fires or floods – to support the rapid metabolism characteristic of passerine birds.

Since the marsupials are generally relatively small-brained and are more prominent in Australia than in South America, it seems that mammals and passerine birds show converse patterns on the two continents. Where the mammals are of inferior intelligence, the passerine birds seem to be of superior intelligence – which is food for thought.

***

All text and images appearing in this blog are subject to copyright, except those images explicitly stated to be in the public domain. You are not free to use any photographs, for any purpose, without receiving written permission from the copyright holder.

1 defined as suborder Tyranni of the order Passeriformes

2 Passeriformes: Tyranni: Pittidae

3 Corvus, Corcorax, Colluricincla, Falcunculus, Daphoenositta and Ptilonorhynchus

4 We exclude from tool use the practice of ‘anting’, defined as the holding of ants in the beak while preening. Anting occurs in various South American birds and has also been recorded in Australia, albeit surprisingly seldom.

5 We expect, however, that South American thrushes (Turdus) will prove to use stone anvils for breaking snail shells as this genus does on other continents.

6 Passeriformes: Icteridae: Psarocolius

7 Passeriformes: Icteridae: Molothrus

8 Passeriformes: Passeri: Menuridae

9 Ptilonorhynchidae

10 Passeriformes: Cracticidae: Gymnorhina tibicen

11 with the possible exception of manakins and certain other Cotingidae

12 Passeriformes: Corvidae: Corvus, usually relatively large species

13 Passeriformes: Corvidae: Corvus, usually relatively small species

14 Passeriformes: Cracticidae: Strepera

15 Passeriformes: Corcoracidae: Corcorax melanorhamphus

16 Passeriformes: Menuridae: Menura novaehollandiae; Australian scrub-birds (Atrichornithidae), related to lyrebirds, have yet to be investigated for brain size

17 Corvus coronoides

18 Passeriformes: Icteridae: Psarocolius bifasciatus

19 Passeriformes: Corvidae

20 judging from a close relative in central America which has a body mass of 377 grams and a brain volume of 5.9 cubic centimetres

21 Passeriformes: Corvidae: Corvus bennetti

22 Passeriformes: Corvidae: Corvus mellori

23 Rattus norvegicus

24 The southernmost jays are species of Cyanocorax.

25 Triodia, a genus widespread in but restricted to Australia