These woodheads would rather burn at the stake than be called pines or oaks.

Robin: Welcome, Casuarina, to our interview series here at Exploring the Bio-edge. In our series we encourage originality, and you seem to have a particularly lateral approach to growing tall.

Casuarina: Thank you for having me, Robin and the Honey Badger.

The Honey Badger: Can you introduce yourself for general listeners? You’re as similar as flowering plants get to a gymnosperm, not so?

Casuarina: Well, I’m a group of trees and shrubs native to Australasia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and the whole of Indonesia. And don’t forget that isolated island in the western Pacific, New Caledonia. You’re right, Honey Badger, I do resemble true pines in having a conical shape as a juvenile tree, needle-like foliage that either droops or stands up rigidly, cones for the protection of my seeds, pollination by wind, and a tolerance for poor soils. But I don’t like being mistaken for pines because any similarities come not from my family tree but from where and how I make a living. My ancestors were related to alders and birches but I couldn’t have succeeded in my present range without some serious makeovers. So I’ve taken a few useful leaves out of the pines’ book over the years simply because they worked for me as part of these adaptations.

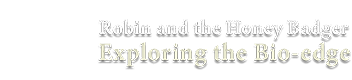

The Honey Badger: Haven’t I heard you being called ‘sheoak’ and ‘desert oak’ as well (see Figure 1)?

Casuarina: Australians do use those names but that’s also misleading, because I’m no more related to oaks than hazelnuts are.

Robin: So how do you operate differently from the true pines of the Northern Hemisphere?

Casuarina: Well, for one thing, I grow as rapidly as pines but without making my wood flimsy as most of them do. On the contrary, some of my wood is heavy enough to sink in water even when dry, and the rest is at least as dense as ‘heart of oak’, yet I pile on wood as quickly as softwoods do. In the form of beach casuarina – which some humans call whistling pine – I’ve recently spread to tropical coasts across the Indian and Pacific Oceans because I can grow even on poor semi-saline sand and reach up to 40 metres high in a few decades. Admittedly, I’ve actually become a ‘problem plant’ in Florida, and the government is trying to wipe me out there even though it was humans that deliberately took me there in the first place.

Figure 1. Desert oak (Allocasuarina decaisneana) in its semi-arid habitat in central Australia, showing a fully mature tree with some senescing branches [photo by Ruth Palsson].

Robin: With the rapid growth of your woody trunk, it almost sounds like your mission in life is to make wood for wood’s sake?

Casuarina: I realise it may be hard to understand a photosynthetic mind, but if I have a mantra it’s ‘lignin’. Sure, pines are great for cellulose and resin, but the more lignin my body can make, the hardier I get. Some of my species are even called ‘ironwood’. Come to think of it, I haven’t heard a decent ecological explanation of why some fast-growing trees, like mine, have dense wood, while others, like pines, have light wood. I’ll leave the scientists to keep pondering that one …

The Honey Badger: And humans have established plantations for your wood?

Casuarina: Far and wide.

Robin: What makes your timber so desirable? Is it the amount or the type?

Casuarina: Both, really. Some humans describe me as the world’s best in terms of quality and quantity of firewood. Combining fast growth with dense wood is hard to top. But I wouldn’t exactly call my wood ‘timber’ because it’s not used for construction on any scale. It cracks too much when drying out and is hard to make into planks.

Robin: So what’s so special about your particular wood then?

Casuarina: Well, I’m one of the few woods out there that is noteworthy for fuel and at the same time so good-looking that humans often feel regret when tossing it on to the hearth. My polished wood looks a bit like marbled steak, which has led to the colloquial name ‘beefwood’ for some of my species.

The Honey Badger: So humans have compared your foliage and cones to those of pines, and your wood to oak, iron, and meat. Common names are confusing and I guess that’s why scientific names are so essential. But, coming back to your wood, in which ways do you excel as fuel?

Casuarina: I guess the surprising things are that my wood is so easy to cleave down the grain with an axe and so flammable that it easily catches fire even when fresh and moist. For those reasons, my plantations are very useful in deforested countries such as India and China.

Robin: But are you actually superior to pine for these humans?

Casuarina: The locals find me better than any pine because my dry wood burns so intensely that one block of it will boil two pots of water for every one pot boiled on a block of dry pine wood – and what’s more, there’s minimal ash to clean up. A bonus is that humans can also kindle a fire easily with my litter, which is as flammable as pine needles, and then just throw on pieces of my fresh wood in its ‘green’ state once the fire is on its way.

The Honey Badger: And coming back to quality, how do humans turn this fuelwood to some kind of woodworking as well?

Casuarina: I’ve got a quirky wood grain with wavy planes and speckles, similar to protea wood, but with a more tightly interlocked grain, and a hardness to rival acacia or eucalypt wood. This combination is a problem for wood-chipping machines, because it judders and blunts the blades. It is even difficult just to saw through my logs, because saws tend to heat, chatter, and veer off-course. It’s almost a case of ironwood beating steel. But on the other hand, the easily-splitting planes fall apart without difficulty if humans just use an axe to chop fuelwood or split logs into roof tiles. And, let me tell you, those tiles are worth cleaving owing to their durability. Also, if you don’t mind me giving myself another polish on the back, I must say that the grainy look of my wood can make quite an attractive finish on small items of furniture or craftwork.

The Honey Badger: Are you resinous, like pines?

Casuarina: Strangely enough, I’m not. I live with eucalypts that are flammable because of their leaf oils; and like eucalypts my crown will explode, and not just scorch, in a wildfire. But I manage to put off insect pests without making smelly chemicals. This is partly because I keep myself poor in the trace elements that animals like, even when I grow on relatively rich soils like lava or the mud adjacent to mangroves.

Robin: So how do you arrange for your leaves and wood to be flammable before they even dry out, if you don’t use the resin of pines or the volatile oils of eucalypts as self-incendiaries?

Casuarina: Biochemists have yet to investigate this but here’s a clue: new research into the metal called manganese might just spark some interesting insights. This is a powerful oxidant and although it’s usually assumed to be a trace element it’s common enough in my habitats to have potential as a fire-promoter in my foliage and wood. But another hint: don’t necessarily assume that I also lace my cones with this element; remember that my cones are the one part of my body I don’t want to burn because they contain my seeds.

The Honey Badger: It is your needles that look particularly similar to those of pines; so how exactly do they differ, apart from lacking resin?

Casuarina: The similarities between pine-needles and my polyplicodes are only superficial, and the differences have nothing to do with the fact that I’m technically a flowering plant.

Robin: What did you just call your needles? Polyplicodes?

Casuarina: Yes, it’s a new name because none of the old names fit me. Pine needles are just leaves, no matter how narrow and fibrous. But my polyplicodes – let’s just call them cas-needles for now – are actually miniaturised stem systems, complete with miniature leaves, so narrow that they’re hard to see even up close. You often hear that my leaves are vestigial in the form of the tiny brownish scales located at my nodes. But that’s silly, the things at the nodes are just brown bracts. I’m not degenerate, I’m just subtle.

Robin: Your foliage still has us a bit foiled.

Casuarina: Well, my leaves, which we can call leaflets although each one arises directly from the stem, are so narrow and so fused to my stems that it takes a microscope and cross-sections to see that they are leaflets at all. The end effect seems to be just a streaky green coating on thin twigs, which are lax and pliable in some species and stiff and spiny in others. Indeed, my coated twigs look deceptively like pine needles (see Figure 2).

The Honey Badger: How miniature are we talking?

Casuarina: In one of my typical species each cas-needle comprises about one hundred tiny, linear, adhesive leaflets growing from a series of internodes. Up to 20 of these barely visible leaflets, each no wider than a thread, are fused side-by-side around each internode stem, which is no thicker than spaghetti.

Figure 2. Long-leaf ironwood (Casuarina glauca), showing the polyplicodes (cas-needles) in general view and in detail. Each polyplicode consists of a long series of nodes and internodes. Within each internode, 10-12 green ridges (the leaflets or phyllichnia) are arranged around and adhere to the stem [photos by Forest and Kim Starr].

The Honey Badger: So beach casuarina is not actually as threadbare as it looks?

Casuarina: That species may look threadbare but some of my other tree species look quite full-bearded in a grizzled kind of way. Anyway, silk may look threadbare to someone used to hessian or burlap, if you see what I mean.

Robin: Point taken.

Casuarina: And no offence to botanists, but I just feel a bit understudied given that I do present this paradox of apparent – and I mean only apparent – leaflessness but really rapid photosynthesis. These days we hear of nano this and nano that and nobody would say that silicon chips are some sort of vestige just because they’re small. And it’s also obvious that I must be getting lots of power somehow to be able to grow so fast. But physiologists seem to have been a bit slow to solve this riddle of mine, of a kind of leafless wood factory. If all that pines had come up with was a needle leaf and you had instead invented this whole miniaturised stem system of foliage, earning compound interest on solar power, wouldn’t you want a bit of recognition for that?

Robin: We take your needle.

Casuarina: (smiling) Anyway, pines have succeeded in plantations in Australia but they wouldn’t survive long-term in the wild, what with trace element deficiencies and erratic weather.

The Honey Badger: You mean with that whole on-again off-again El Niño climatic pattern?

Casuarina: Yes, pines pride themselves on being evergreen but are not particularly resilient from drought. This is where I have the edge. My leaflets have been reconfigured to shift the stomata off the green surfaces. I’ve placed them in the tiny waxy, and in some species hairy, grooves that run down the cas-needles, which are technically the surface of the stem, not leaf. What this means is that in drought I can shut down photosynthesis and the stomata are sealed by wax and hair. My radical design means that the cas-needles can turn brown in a living state during drought and then go green again without being shed as they are in the deciduous, broad-leafed alders and birches. Some of my species are actually resurrection plants in that sense.

Robin: Switching from full activity to seasonal dormancy without wilting? You’re talking about diallagy, right?

Casuarina: Yes, that’s what humans are now calling a kind of reversible dormancy. It’s a combination of resurrection and lignification of foliage that certainly took some lateral thinking to evolve. In one of my southwest Australian shrubs, called tamma, the olive-green foliage turns brown, red, or purple each dry season – but the same long-lived cas-needles revert to my usual dull green each rainy season. What would seem to Americans to be ‘fall colours’ here turn out to be the opposite: a sign of how durable my foliage is.

The Honey Badger: Strange that it took humans until so recently to notice this phenomenon.

Casuarina: Yes, in fact one species of mine qualifies as perhaps the biggest resurrection plant of any kind, worldwide. No pine can be called any sort of resurrection plant, that’s for sure.

The Honey Badger: How do cas-needles help you to produce so much energy for your wood, given that some of your species look so droopy and half-green that humans might not even say you have foliage? Can you help us picture this?

Casuarina: Okay, let’s see, I’m speaking as a self-botanist here. You could perhaps think of my foliage as a system of batteries linked in synergistic ways that conserve nutrients, with all the dimensions reduced to the point that some humans don’t see foliage at all. It’s partly a case of each cas-needle working slowly but steadily for years. Because I keep photosynthesising in all seasons, the Joules add up. But you have to remember about economies of scale too. Because each cas-needle consists of several miniature internodes and each of those has several even more miniaturised leaflets, my foliage works, I suppose you might say, like a whole lot of batteries arranged in series as well as in parallel. Picture a tall tree with each of its drooping stems comprising thousands of tiny green panels arranged inconspicuously because they coat such a small circumference. Can you see that the total number of photosynthetic units might be as many as in a tree like a mimosa, but without the mimosa’s losses to insects and drought?

The Honey Badger: Sounds almost as complicated as string theory. Are governments eyeing your foliage design as a new green technology?

Casuarina: Actually, I don’t think even the botanists have twigged on to it yet.

Robin: Now, to change the topic: by the sound of it, you’re not very generous to animals, are you?

Casuarina: Insects, definitely not, at least while I’m alive. And no offence, but I don’t go out of my way for birds either. I haven’t designed my pollen for animals because, like pines, I get pollinated by the wind for free. Although wind-pollination also occurs in many other plants, I’m unusual because each of my individual plants produces either pollen if a male or seeds if a female, but not both. And what is more, other lineages of trees and shrubs that have separate male and female plants tend to be pollinated by animals of various sorts. My pollination results in cones that are like small versions of pine cones and it’s true that I’m particularly tight with them. Small so-called seeds eventually fall out of these cones, often only after the plant dies. But, because only half of the trees are female, even a forest of casuarinas produces relatively few seeds.

The Honey Badger: Why did you say ‘so-called seeds’?

Casuarina: What actually drop from my cones are not seeds, as in the case of pine cones, but samaras, which are actually miniaturised dry fruits. Each samara contains no more than one small seed and some are ‘blanks’ with no kernel at all. In the case of beach casuarina, the cones can float until washed on to shore, then open to release samaras blown inland by sea breezes; as an aside I don’t know of any pine that can cross the sea in this way (see Figure 3).

Robin: Do animals treat your samaras differently from pine seeds, which can also have wings?

Casuarina: Well, certain pines make large seeds on such a scale that pine nuts are a commercial crop in some places and, by contrast, my seeds are so small that few animals larger than ants find them economical to extract from the samaras. The pines also squander their seeds on all manner of freeloaders, such as jays, squirrels, and even woodpeckers, in the vague hope of getting dispersed and sown in return, but I don’t need to sell out. Frugality works for me because my samaras, although few, are light enough to be blown as far as they need to go to give my offspring a good start. But, coming back to birds, don’t forget that at least one species of cockatoo, the glossy black cockatoo, does actually concentrate on extracting my seeds directly from the cones as its staple diet – to my loss.

Figure 3. Desert oak (Allocasuarina decaisneana) and pine (Pinus), showing a comparison between the cones of the flowering plant and those of the coniferous gymnosperm [photos by Ruth Palsson and Sussman Imaging www.sussmanimaging.com, respectively].

The Honey Badger: Okay, you may lose some seeds to a cockatoo or two, but pines lose a lot more to various seed-destroying animals. I’ve heard the thick-billed parrot specialises on the seeds of pines in Mexico, and crossbills are parrot-like finches that extract the seeds of pines in Canada and Russia. Isn’t it true that even in Australia, in commercial plantations of pines, cockatoos quickly learn to take advantage of the big seeds? If that means they never look back at casuarinas, you’re lucky.

Casuarina: I know it may seem grizzly to begrudge minor losses, but making ends meet can be precarious in my habitats – particularly for nutrients such as the phosphorus and zinc so essential for making seeds.

Robin: It’s not that I care much for honey myself, but I have winged friends who get lots of nectar from eucalypts and even a bit from wattles, and they say they’ve never found a drop of sweetness on you. Sorry, but they used the word ‘miserly’.

Casuarina: Well, it’s true. I don’t have a saccharine relationship with animals, even though I often grow among plants like banksias and other proteas that splurge with nectar. I don’t have floral or extra-floral nectaries, and my flowers are small even compared with other dry plants. Although I’m wind-pollinated like my cousins the alders and birches, I make just one stamen compared to their 2 to 12 stamens, per male flower.

Robin: Do you feel that most Australian trees and shrubs pay too much for pollination?

Casuarina: I do. They waste sugar that could be made into lignin instead. No offence to you, Honey Badger.

The Honey Badger: Actually, contrary to my reputation, I don’t care much for honey.

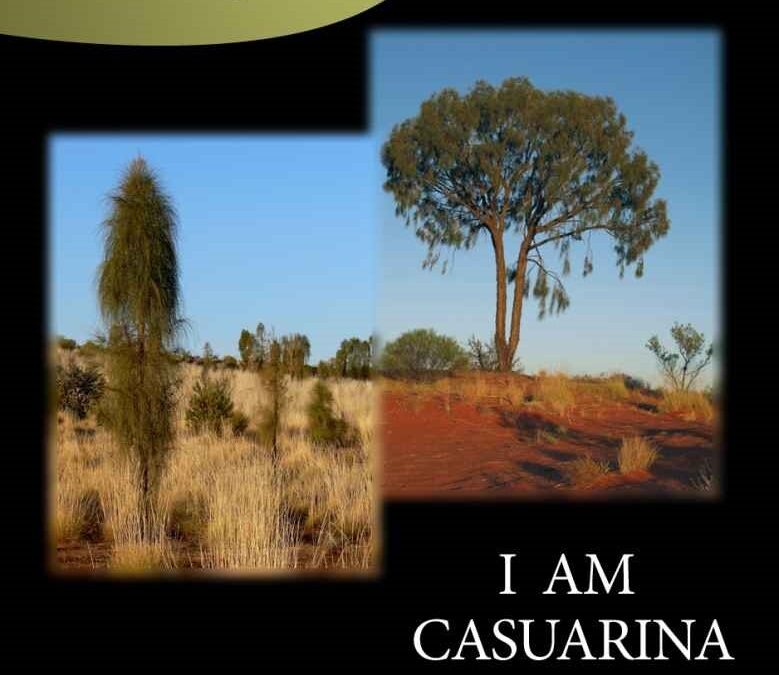

Casuarina: Anyway, if I was that careless with my energy and water I wouldn’t be able to grow as the so-called desert oak, the only tall tree on the sands around Uluru in the arid centre of Australia (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Desert oak (Allocasuarina decaisneana) in its typical habitat in central Australia, showing how the saplings grow tall rather than broad [photo by Genet at the German language Wikipedia under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported licence].

Robin: What about herbivores?

Casuarina: Sundry large herbivores nibble on me sometimes. Although my foliage is nutrient-poor and astringent, at least it’s not toxic. One of the few mammals I’ve experienced browsing in my crowns is the New Guinea mountain cuscus, but even that species didn’t seem to find my foliage tasty. I noticed that it swallows only the softer tissues, ejecting the rest from the sides of its mouth as an almond-shaped pellet. That’s presumably because not even cuscuses – despite being related to the koala – can digest lignin. Australian arboreal marsupials such as possums seem to find my tissues too meagre to bother with and they enter my groves only in search of mistletoes. And that reminds me of something funny, albeit slightly off-tack …

Robin: Please.

Casuarina: Several kinds of mistletoe grow on me. Although these are parasites, I find it amusing that one of them actually mimics my foliage form, pretending to have cas-needles, when in fact it has longer leaves than other mistletoes. Although I don’t taste good to caterpillars, this mistletoe does, and the egg-laden female butterfly flies around in vain, baffled by a disguise that would not fool any botanist.

Robin: Getting back to exudates, what about bark gum, like the edible gum of some wattles?

Casuarina: I know that the trunk of sugar pine produces lots of sap edible even to humans, and other pines in the Northern Hemisphere support lots of sap-sucking aphids and the abundant ants that drink ‘honeydew’. That’s just aphid pee with a fancy name, by the way.

Robin: Yours is a dry humour …

Casuarina: (smiling) Anyway, sounds like a sickly way to live. I keep my sap so poor in trace elements that it discourages even the psyllid bugs that replace aphids on eucalypts and wattles. Another group of sap-suckers called triozid bugs are among the few who can put up with my frugality. Sometimes I produce small amounts of a manna-like substance from my unripe cones. But this can’t compare with the copious manna produced by the salt-cedars of dry parts of Eurasia, or by pines for that matter.

The Honey Badger: You sound almost as dogged as me when it comes to getting nutrients in unpromising places.

Casuarina: Well, yes, when it comes to my roots I don’t believe in leaving any stone unturned.

The Honey Badger: It’s a good thing for you that I’ve never been in your habitat, or else I would have dug up your complex underground network. I hear you have a whole mining and refining operation down there?

Casuarina: Yes, I’m glad my habitat doesn’t overlap with yours – or that of any species of badger, for that matter. Anyway, my emphasis on roots is another reason that it’s silly to call me after pines or oaks, which seem unimaginative by comparison. I’ve got two quite different kinds of symbiotic root fungi, plus nodules housing a bacterium that fixes nitrogen from the air, plus cluster roots which mine the litter for phosphorus. And some of my species growing in wet places resemble mangroves in having air passages into their roots.

Robin: Versatile for sure, but are any of these root adaptations unique? I’ve heard that pines also starve any herbaceous plants trying to grow under them.

Casuarina: No one of them is unique, but I haven’t heard of any other plant combining as many underground tactics simultaneously as I do – and pine and oaks don’t even fix atmospheric nitrogen. Come to think of it, can anyone name another wind-pollinated, dioecious plant, apart from me, that can fix atmospheric nitrogen? Funny kind of distinction, but I think I’m the only one. Worldwide, nitrogen-fixing plants are mainly legumes with hermaphroditic, insect-pollinated flowers. And another point: pines may benefit almost as much as I do from robust root-fungi, but their fungi such as boletes waste resources by making mushrooms which are harvested by deer, bears, squirrels, and humans.

The Honey Badger: So you’ve made accomplices of certain root fungi that work economically together with bacteria in your scheme to get as much nutrition as possible and give as little of it away as possible?

Casuarina: Precisely.

The Honey Badger: Listeners might appreciate some love interest. Is there anything you’re prepared to share?

Casuarina: Well, I may not be sexy but at least I can be original with my genders. In a species of mine, compass bush, the female shrubs can at a distance easily be distinguished from the male shrubs because they are taller and lean automatically to the south without any pressure from wind. This species has particularly stiff-looking foliage and resembles a stunted, wind-battered pine. But it doesn’t grow in a particularly windy area and none of the plants around it are shaped by wind. Most humans take it for granted that males and females of dioecious trees and shrubs look similar, yet in the case of compass bush the females are like a kind of living compass and the males aren’t.

The Honey Badger: And how does this sexual dimorphism help the females?

Casuarina: That’s another thing for the scientists to ponder.

The Honey Badger: So you prefer woodwork to romance?

Casuarina: I know that sounds strange, because plants can get animated about things that leave non-photosynthesizers cold.

Robin: (smiling) Try us.

Casuarina: Well, animals and even many plants may not get this but I actually love fire. I look forward to the day I burn down because I know that my wood-ash, although minimal in volume when compared to some other tree species, will provide key resources for my offspring in an equivalent way to your yolk or placenta. I’m one of those plants the ecologists call ‘pyrophilic’, which almost sounds like some sort of perversion. Several of my species retain their seeds in sealed cones for years until after a wildfire has passed, when the cones open to shed the samaras on the nutritious ashes.

Robin: We see, so fire means babies?

Casuarina: Well, one of the payoffs of growing in eucalypt forests as I often do is that sooner or later there’s going to be a firestorm, or, from my point of view, a blaze of glory. I grow rough bark that, over the years, accumulates a lot of fallen cas-needles and dehisced cones in the branch-crooks of my trunk. That helps to fire me up enough to burn me down even if the fire is relatively mild.

The Honey Badger: Many eucalypts make a kind of chimney of themselves by allowing termites to hollow out the heartwood of the living, healthy tree. You know, the didjeridu thing. And then a fire can consume the tree from the inside out as well as from the outside in.

Casuarina: You’re right, nobody’s made a didjeridu out of me, because termites don’t hollow out my trunks or branches in that way while I’m alive.

Robin: So how do you arrange for breakdown of the dead trunks that do remain after a lethal fire, which sound so durable that they could stand around cluttering up the habitat for years?

Casuarina: Well, I do try to burn down as thoroughly as possible to release my nutrients for the next generation. As I mentioned, some of my forms have thick bark, but this is pyre as much as protection. Even if the fire is just an understorey smoulder, flames can climb my trunk, burning holes deep into my heartwood. And, as a further measure, in death I switch from durable wood to perishable wood.

Robin: How does that work?

Casuarina: After I die my wood contains just enough nitrogen that, given its lack of chemical toxicity, it becomes attractive to fungi, termites, and wood-boring insects. So it tends to be consumed fast, compared to eucalypts for example. That’s another reason why I’m not much use for timber, or even fence-posts.

Robin: You do seem to think outside the box, don’t you?

Casuarina: I’ll take that as a compliment, coming from you two.

The Honey Badger: Do you actually try to die after getting scorched?

Casuarina: Well, sometimes I do survive and refoliate from buds under my bark. And some of my species grow in places like beaches, or the volcanic mountains of Java, where fire is unlikely. But even a beach casuarina tends to die after nothing much worse than a taste of ash in its roots when humans make a camp fire on the ground under it. My fire-free habitats tend to be places subject to other catastrophes, such as floods and landslides. In fact, I thrive on volcanoes such as Krakatau, where it was my trees that were the first to colonise lava, ash, and landslides. I guess I’m a catastrophist first and a pyromaniac second, an attitude I share with eucalypts.

The Honey Badger: We get that you don’t view the fire thing as half-incineration, you view it as half-fertilisation. And that’s because your seeds germinate and grow best after fire and your saplings try to distance themselves from the understorey as rapidly as possible, so that they can produce their own seeds before the next fire.

Robin: A truly refreshing strategy there, Casuarina. So, rising above all the details, can you give us a bird’s eye view of your approach to life?

Casuarina: Well, I choose habitats with few herbivores and manage to be boring to those that are present. I don’t mind if I seem ungenerous, because that way I can keep just enough nutrients in my foliage to run a solar-powered lignin factory, but not enough to attract animals. I am one of the most deceptive of trees above ground and one of the most multi-talented below ground. I keep stockpiling wood every day of the year if I can. My cas-needles continually recharge with energy without me having to shed and regrow much foliage. And even though I’m not as obvious about it as eucalypts are, I am married to fire, which is a way of recycling nutrients to my next generation.

Robin: Keep going …?

Casuarina: If we want to get a bit abstract, think of me as a plant with different dimensions above and below ground. Above ground I’ve reduced my dimensions in two ways. Miniaturisation plus each cas-needle being almost two-dimensional like a string. Below ground, I’ve actually increased my dimensions in two ways: having deep and broad roots and exploring a large volume of soil with both roots and various invisible allies.

The Honey Badger: Which goes to prove that photosynthesizers can have synthetic minds.

Robin: Any final comments?

Casuarina: Just another word on what to call me. North Americans say ‘Australian pines’. But actually I’m more widespread in southeast Asia and the Pacific than in Australia. Even Australians tend to overlook the fact that I’m naturally absent from nearly half of Australia. So all the existing vernacular names are somewhat inept. Please, everyone, just call me CASUARINA.

Acknowledgements:

Our sincere thanks to David Brewster and Ruth Palsson for permission to use the photos of juvenile and mature desert oak (

***

All text and images appearing in this blog are subject to copyright, except those images explicitly stated to be in the public domain. You are not free to use any photographs, for any purpose, without receiving written permission from the copyright holder.

Casuarinaceae: Allocasuarina huegeliana, another tree native to southwest Australia