Note to readers: Biological Expositions is a series of blog-posts each of which is equivalent in content to a book chapter. If bio-bullets are likened to a starter, blog-posts could be seen as a light lunch and Biological Expositions as a three course meal.

One drought-beating tree with an aura of affluence can wear its crown of thorns as a halo.

Robin: The Honey Badger and I would like to welcome you, Umbrella Thorn, to our plant interview series here at Exploring the Bio-edge.

Umbrella Thorn: Thank you for this opportunity for promotion among your animal friends.

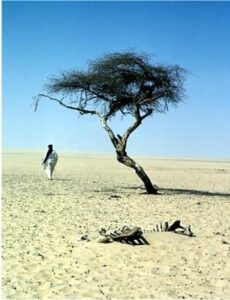

The Honey Badger: ‘Icon’ is an overused word, but you really are the picture of gorgeous African savanna, aren’t you?

Umbrella Thorn: Well, I’m one of about five species with that distinctively African profile (see Figure 1). But I am the one most typical of the real big game country of Africa, because it is my celebrated silhouette that catches the eye in photographs of the Serengeti, Amboseli, and Kruger National Parks.

Figure 1. Umbrella thorn (Vachellia tortilis), showing the mature (top) and juvenile (bottom) forms. The mature tree is effectively free of spinescence; the juvenile is spinescent as advertised by the conspicuous paleness of the stipular spines [photos by David Bygott, and MD Hepplewhite and Witkoppen Wildflower Nursery, respectively].

Robin: Just to pre-empt any confusion, taxonomists sometimes have to change scientific names with new information, even though consistency is a goal of taxonomy. I understand that you’ve just recently been rechristened?

Umbrella Thorn: Yes, I’ve switched to Vachellia tortilis after being called Acacia tortilis for many years. Far too many species of acacias – 1,350 at last count – have banked up in one genus based on a common design of the flowers, despite being different in other ways. So now I’m classified only with those acacias that are particularly similar to me.

The Honey Badger: Mmm … Acacia. How do you feel about losing such a familiar name?

Umbrella Thorn: I don’t feel stripped of my identity just because I’m no longer an Acacia. After all, informally I can still call myself an acacia with a small ‘a’. But some biologists have taken my change as a funeral rather than a christening – maybe because my closest relatives and I have long held the spot as the archetypal acacias. Now it looks as if it may be Australian wattles that instead retain the scientific name Acacia. Some pro-Africa botanists see this as a betrayal and they’re calling for ‘wattle wars’ over the taxonomy.

The Honey Badger: So you see yourself as ‘a rose by any other name …’?

Umbrella Thorn: Yes, that’s the way I’d look at the change. But I do understand a reluctance to start calling me and my kin ‘flat-topped vachellias’.

The Honey Badger: Some of your vernacular names have already been downright derogatory, haven’t they?

Umbrella Thorn: Which ones? I’m mentioned in the Bible and even today I’m named more than twelve different ways in just one Arabic dialect – a bit like how the Inuit have many different terms for describing snow.

The Honey Badger: Well, I’m thinking particularly of the Afrikaans ‘haak-en-steek’, which means ‘grab and stab’. It can hurt to be branded as a randomly aggressive sort.

Umbrella Thorn: And I thought you were the thick-skinned one. Actually, I’ve always taken the Afrikaans name to mean ‘hook and stick’. That seems apt enough because my tasty foliage gets my consumers hooked and I’m heaven on a stick for many leaf-, flower-, fruit-, and seed-eaters from bugs to elephants. After all, I have a mutualistic, not antagonistic, relationship with animals.

Robin: Surely you can’t be serious? You look almost like barbed wire in combining two types of thorns, and your whole body language seems off-putting to the herbivores that crowd you. And if you’re not an aggressive plant, why is it that the Maasai cut your branches to make fences for lion-proof cattle kraals?

Umbrella Thorn: Arguably I have as many as four different types of so-called thorns, all varying in shape and size (see Figure 2). But it’s easy to miss the point of my spines and prickles. I love being nibbled and kissed by herbivores but some boundaries have to be set. What looks like barbed wire is just my way of keeping the largest and greediest types from taking advantage of my good nature, so I police the consumers for their own good. In point of fact, my crown loses all its long spines once it’s above the height of giraffe and African elephant, even though it remains a foraging pad for monkeys and baboons. That’s because I only produce conspicuous spines in response to someone actually breaking my stems.

Figure 2. Umbrella thorn, showing the two main types of ‘thorn’ on juvenile plants. The stipular spines are straight and longer than the leaves (top). These spines persist to some degree on stems too thick (diameter more than 10 centimetres, centre) to produce foliage or flowers, where they continue to discourage branch-breakage by the elephant. The epidermal prickles are curved and shorter than the leaves (bottom, and also see Figure 6) [photos by MD Hepplewhite and Witkopppen Wildflower Nursery (top and bottom), and Antonie van den Bos (centre)].

Figure 2. Umbrella thorn, showing the two main types of ‘thorn’ on juvenile plants. The stipular spines are straight and longer than the leaves (top). These spines persist to some degree on stems too thick (diameter more than 10 centimetres, centre) to produce foliage or flowers, where they continue to discourage branch-breakage by the elephant. The epidermal prickles are curved and shorter than the leaves (bottom, and also see Figure 6) [photos by MD Hepplewhite and Witkopppen Wildflower Nursery (top and bottom), and Antonie van den Bos (centre)].

Robin: So, contrary to appearances, you’re far from defensive and aloof?

Umbrella Thorn: I know my crown seems to levitate into a flat canopy as I grow, but I’m not trying to look down on herbivores as much as maintain a solar energy panel. And if I have a rough side that’s just to keep my meristems and shoots intact so that I can continue to pump out food – in the form of leaves, flowers, fruits, and seeds – for animals to eat. In my juvenile form, my spines slow down perpendicular plucking and my prickles block lengthwise stripping, and this works even on the elephant, which has a surprisingly sensitive skin and mouth.

Robin: So your spinescence has a sort of benign duplicity to it?

Umbrella Thorn: Or a multiplicity, as I pointed out before. Several other species of acacias have both spines and prickles on the same branch, so I’m not unique in having more than one type of ‘thorn’. But I am unique in my combination of features: worldwide, I’m the only flat-topped tree, sown by hoofed mammals, that has multi-facetted spinescence without hollow spines for housing ants.

Robin: I haven’t previously heard you described quite so categorically.

Umbrella Thorn: Coming back to the functions of my spines: the lips and palate of the giraffe are too tough for me to harm, but I can nevertheless put the brakes on defoliation with my kind of friction. Rather than impaling any mouth, my spines and prickles act as a drag, slowing even the biggest browsers as they progressively remove my greens. And if the giraffe resorts to chewing me, spines and all, this just dilutes the food value it gets from me. So animals (see Figure 3) are welcome to skim my profits as it were, but then they’ll find it easier to move on to the next individual, which spreads out the trimming effect rather than depleting any one plant.

Figure 3. Umbrella thorn, showing three ruminents which coexist in Kenya and can browse the same individual plant as it grows. Kirk’s dikdik (Madoqua kirkii, ca 4 kilograms) (left) reaches up to 1 metre above ground; gerenuk (Litocranius walleri, ca 35 kilograms) (centre) reaches to 2 metres above ground; and the giraffe (ca 1 tonne) (right) reaches to 5.5 metres above ground [photos by David Bygott]

The Honey Badger: What is your relationship with ants, which certain other acacias use to defend themselves against the elephant?

Umbrella Thorn: Well, most acacias love being tickled by ants, and I’m typical enough in that respect. I have a give-and-take relationship with ants but I’m not like some other acacias, which do them the special favour of giving them hollow spines in which to shelter. Like most acacias I allow certain bugs to suck my sap, tended by ants which eat the honeydew excreted by these small insects. And I have extrafloral nectaries, on my leaf-stalks, which ooze some sugar directly for ants to make sure they patrol my actual leaves. The ants help me by policing caterpillars, but I tolerate plenty of leaf-eating insects nonetheless. It’s more my love of feeding mammals, including the elephant, that sets me apart from other acacias.

Robin: But surely you disappoint browsers by going bare each dry season?

Umbrella Thorn: Other African acacias may be guilty of that but I’m not. I usually keep a green crown through most of the dry season when the plants around me are withered and brown. But this tends to be misunderstood because the English language doesn’t have a word for my kind of seasonality. I’m neither ‘evergreen’ nor ‘deciduous’, but the best of both worlds.

Robin: Could you please explain?

Umbrella Thorn: We acacias differ greatly in the rate of turnover of our photosynthetic surfaces. In Australian wattles the same leaf, leaflet, or phyllode can last for several years. In my case, I grow and discard leaves and leaflets several times within a season.

Robin: And that makes you more productive for browsing herbivores?

Umbrella Thorn: Yes. ‘Evergreen’ doesn’t describe me because I don’t hang on to leaves as evergreens do. Nor does ‘deciduous’ describe me because I keep bearing leaves in normal dry seasons. I’m not like European evergreens such as pines and holly that have leaves so tough and unpalatable that they last all year. Nor am I like European deciduous trees that withdraw the nutrients from leaves before shedding them. Instead I continually drop my tender leaves in a green state without even bothering to withdraw their nutrients first – rather like a lawn in the habit of losing clippings. I grow round after round of these small leaves one after another from the same length of stem, whether I’m browsed or not and even when it is so dry that other trees have shed all their leaves. That means reliable food for leaf-eaters whereas most true evergreens are fibrous and unpalatable. Plus my still-greenish fallen leaflets can be gleaned from the ground as tasty litter, whereas truly evergreen leaves usually remain out of reach on trees.

Robin: So the leaves you’re continually kissing goodbye may as well be nibbled up by whoever can benefit from them?

Umbrella Thorn: Yes, I like to think of my leaflet-litter as a nourishing confetti. The same applies to my copious whitish flowers (see Figure 4).

The Honey Badger: You produce flowers during the dry season too?

Umbrella Thorn: No, I don’t. Some other acacias do produce flowers in the dry season when they’re bare of leaves, but I produce mine at the height of the rainy season, again from pre-existing stems. My point was that although my flowers are small, I produce them generously, beyond my own reproductive needs. And these too rain on to the ground to feed sundry small mouths, such as that of the steenbok.

Figure 4. Umbrella thorn, showing the profusion of flowers in a normal season (left) and detail of the inflorescences (right). Each length of stem generates repeated rounds of inflorescences and leaves from the same nodes, year after year [photos by David Bygott, and MD Hepplewhite and Witkoppen Wildflower Nursery, respectively].

The Honey Badger: Why do you flower in the rainy season? Is it because that’s when pollinating bees are about?

Umbrella Thorn: Actually, I harbour so many different pollen-rubbing insects (see Figure 5) that I would be pollinated even if I flowered in the dry season. And anyway I make far more pollen than is strictly necessary for my reproduction, much of it consumed by various insects. The real reason for my timing is that I want my fruits to ripen at the critical point, so as to fall just when the grass is sparse and brown and the hoofed grazers are leanest.

The Honey Badger: You deliberately cast your fruits before hungry animals?

Umbrella Thorn: Yes, unlike most African acacias and with more dedication than even the other vachellias. And some of the animals I cater to are gracious enough to plant my seeds in suitable open spaces in return. As I said, it’s reciprocal.

Robin: Could you describe your fruits for us? Aren’t they pods as in most other legumes, with cardboard-like walls around a single row of rather hard seeds?

Umbrella Thorn: Yes, they are legume pods, and that means that when ripe they are dry, crisp and hollow, not succulent as in conventional edible fruits. Or even like a green bean, which is actually eaten at an immature stage. The difference is that, unlike the pods of most other acacias and indeed most legumes, mine don’t open when mature. Instead, my pods keep some sugar and starch in the fully dry pod-walls; they retain all their loose seeds; and they’re coiled to make the whole pod easy to pick up off the ground without getting too much grit between the teeth, to which ruminants are sensitive. I also do some advertising: my ripe pods are attractive because they’re fragrant and the seeds rattle inside the pods as they fall to the ground. When the impala smells and hears this ‘dinner announcement’, it drops its grazing and runs excitedly over to my tree (see Figure 6).

Figure 5. Flower beetle (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Cetoniinae), showing one of many species of insects that, collectively, consume various parts of the inflorescences of umbrella thorn while potentially pollinating the small proportion of the flowers that produce pods [photo by David Bygott].

The Honey Badger: Why were you so valued in the biblical lands? Is it because you nourished the flocks with your ripe pods?

Umbrella Thorn: Yes, and I resemble an even more typical Middle-eastern legume, the carob tree, in that way. In fact even the shepherds would eat my pods as a raw snack or a cooked porridge, although of course they couldn’t chew the seeds and had to grind them up using a mortar and pestle first. But in times of famine I may have made all the difference to the survival of tribes living in the wilderness.

Figure 6. Umbrella thorn, showing ripe pods ready for consumption by mammalian herbivores that disperse and sow the seeds. The pods retain a contorted shape in maturity (top), then fall naturally to the ground (bottom), where their shape helps large herbivores to pick them up cleanly one by one. The still-attached pod (left) shows a hole made by a seed beetle (Bruchidius sp.); the fallen pods (right) show a few split examples of the dark, hard seeds [photos by Dr Ori Fragman-Sapir, Jerusalem Botanical Gardens www.botanic.co.il, and Dr Mark A. Wilson (Public Domain), respectively].

Figure 6. Umbrella thorn, showing ripe pods ready for consumption by mammalian herbivores that disperse and sow the seeds. The pods retain a contorted shape in maturity (top), then fall naturally to the ground (bottom), where their shape helps large herbivores to pick them up cleanly one by one. The still-attached pod (left) shows a hole made by a seed beetle (Bruchidius sp.); the fallen pods (right) show a few split examples of the dark, hard seeds [photos by Dr Ori Fragman-Sapir, Jerusalem Botanical Gardens www.botanic.co.il, and Dr Mark A. Wilson (Public Domain), respectively].

The Honey Badger: But how nutritious can your pods be to wild mammals, given that they dry out to a papery texture while ripening?

Umbrella Thorn: Actually, I go out of my way for them. I deposit phosphorus in the pod walls even though a priority is to allocate enough phosphorus to the seeds themselves. Considering that I’m not a particularly phosphorus-rich plant by world standards, the fact that I spend phosphorus in the pod-wall, where it will be digested by mammals but lost to the seedlings, shows how committed I am to feeding the mammals.

The Honey Badger: A phosphorus-rich edible fruit – now that’s a novelty.

Umbrella Thorn: Another reason my pods are easy to misunderstand is because, unlike conventional fruits, most of my hard seeds are meant to be included as part of the digestible content. Analysing the whole fruit makes a difference because there is much more protein, zinc and copper in my seeds than in the ripe walls of my pods, which are in themselves digestible but not nutritious enough to stampede for. The trace elements I just mentioned are as important to the pod-eaters as they are to my seedlings.

The Honey Badger: You mean to say that you actually intend for hoofed animals to chew up and digest most of your seeds, rather than ‘spitting the pip’?

Umbrella Thorn: Yes, and if they do so, then the nutritional value of my whole pod in its ripe state is fairly similar to that of lucerne hay – which more than makes up for the green grass the grazers are missing at that time of year. By and large, animals are not my enemies, and I believe in giving appropriate gifts to my friends. But don’t forget that it takes all types. For example the giraffe – a thorough cud-chewer – seldom defecates any of my seeds intact whereas the elephant can defecate hundreds intact in a single dung bolus, and the grazers are somewhere in between.

Robin: Let me get this straight: in addition to consigning your leaves to browsers, you choose also to consign your seeds to grazers who would never browse you and whom you could otherwise ignore? And you do so in the dry season when other acacias avoid pressure by simply being bare of leaves and fruits?

Umbrella Thorn: Yes, a particular devotion to mammals is almost part of my DNA. For example, something that biologists may not have noticed is that my seeds are seldom eaten by birds, even seed-eating birds such as doves or the helmeted guineafowl. Those that are not picked up by hoofed mammals tend to be snapped up by the various rodents abundant in my habitat.

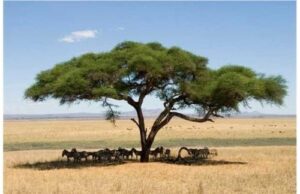

The Honey Badger: I don’t know whether it’s possible to flatter a flat-top, but I have personal experience of your generosity even though I don’t eat any part of you myself. I’ve found that it’s always worth scratching around in your shade or even scrambling up your trunk because my prey animals, such as lizards and scorpions, tend to be commonest in your vicinity.

Umbrella Thorn: Thanks, but I don’t want listeners to think I’m an angel, because I’m not above lacing my leaves with some tannins and cyanide precursors, particularly in drought or when I get rough treatment. After all, I am at some risk of abuse by the world’s richest fauna of large mammals. But turning the other cheek is what usually works for me.

Robin: (smiling) Now that I look at your silhouette again, it’s almost reminiscent of a cross.

Umbrella Thorn: Now you’re getting carried away. An icon is not the same as an idol. However, it is true that one individual, the Tree of Ténéré (see Figure 7), seemed so heroic in its resurrection in the Sahara that it achieved a spiritual significance as a ‘tree of life’.

Figure 7. Umbrella thorn, showing the solitary Tree of Ténéré in the Sahara, reputed to be the most isolated tree on Earth until its death in 1973, when it was accidentally hit by a reversing truck. The location in northeastern Niger, southwest of Bilma, at 17° 45’ North, 10° 04’ East, receives less than 20 millimetres of mean annual rainfall [photo © KrohnPhotos, http://www.krohn-photos.com].

The Honey Badger: Reputedly, that isolated plant survived more than 400 kilometres from the nearest tree. How did it manage that?

Umbrella Thorn: Well, I can push my roots down really deeply when I need to – and in the case of the Tree of Ténéré, more than 33 metres to the groundwater. I can also spread my shallow roots far wider than my crown. I’m as resourceful as any acacia in reaching for a drink and I can also ooze water from my shallow roots to dissolve the nutrients I need to absorb from dry soil.

The Honey Badger: I too believe in mining any opportunity and holding my ground.

Umbrella Thorn: If anyone is looking for wooden effigies, you could liken my form and function to the crook of a good shepherd, intended to steer rather than to harm.

The Honey Badger: Even if it means encouraging the flock to eat your own progeny?

Umbrella Thorn: Well, bear in mind that even if grazers and rodents did not digest my seeds, the small seed beetles abundant in my habitat would soon destroy most of my progeny anyway. I realise that this must sound wooden-hearted to vertebrates like you two, but I make enough offspring to be able to spare most of them. After all, like many trees, I can live for centuries rather than decades, and in that time I only have to replace myself once.

Robin: Surely you could put enough toxins into your seeds to protect them from the beetles, at least? After all, many other legumes are notorious for alkaloids in their seeds.

Umbrella Thorn: Actually, I welcome some infestation because the holes in the seeds help ruminants to break the hard seed-coat and grind the cotyledons into paste. That indirectly helps me to subsidise the grazers who disseminate and fertilise me (see Figure 8), and there are enough intact embryos left in their faeces to allow me to germinate successfully. I suspect that I might actually be worse off without my seed-boring insects. Come to think of it, if I had the choice of losing my foliage ants or my seed beetles, I’m not sure which I’d rather forfeit in the long run.

Figure 8. A herd of plains zebra (Equus quagga boehmi) in the shade of a mature Umbrella Thorn. The tree is fertilised by the urine and faeces deposited by these plains zebra as well as other species of large herbivores.

The Honey Badger: Does your generosity extend to your bark as well, which the elephant sometimes strips?

Umbrella Thorn: No, it doesn’t and ring-barking can kill me. I lace my bark with lots of tannin to make it taste mouth-puckeringly dry. And the gum I produce in response to stem-boring insects is less digestible to gum-eating animals like primates and bustards than that of other acacias.

Robin: Is it you who is the source of gum arabic, that multiple-use exudate exported worldwide from the wilderness of the Sudan?

Umbrella Thorn: No, that’s Senegalia senegal. And it’s not really a wild plant even though it used to be a favourite food of the hook-lipped rhinoceros, which disappeared from most of the range of gum arabic centuries ago. Most of the gum is harvested from shrubs that spring up spontaneously as a fallow after cultivation. The semi-cultivation is part of the reason why the gum arabic plant can afford to ooze such a wholesome gum with such abandon in response to deliberate incision.

The Honey Badger: And what can you tell us about your wood?

Umbrella Thorn: I’m not as ligneous as many other acacias – indeed my wood is unremarkable among trees in general, now that I think about it. My skeleton is softer and more palatable to borers and termites than that of the knobthorn, an acacia that defends itself from the elephant with a painfully spine-studded bark and such a hardy bole that it refuses to snap cleanly even when broken at right angles. But on the other hand, my wood grows too slowly to make me a candidate for a fuelwood plantation. If you want a tropical and subtropical tree that really produces dense wood in quantity, try the Biological Expostion, ‘I am Casuarina’.”>casuarinas of southeast Asia and Australasia – which take the opposite approach from me by shunning animals and hoarding their energy instead. All I care about is that my trunk lasts long enough to support my ‘browsing lawn’ and casts enough shade that wildebeest and other hoofed mammals linger under me long enough to excrete nutrients in partial return for my favours.

The Honey Badger: Considering how hardy you can be, how hard is your wood in fact?

Umbrella Thorn: Listeners may be surprised to learn that my wood is much softer than those of various acacias which don’t even have distinct trunks and instead grow as mere shrubs. My wood is soft for a ‘hardwood’, which means it’s about on a par with longleaf pine, which is one of the harder of the ‘softwoods’. So, foresters have not attempted to classify my wood according to the usual division.

Robin: You liken yourself to a rapidly regenerating lawn for browsers but you say your woody stem is on the slow-growing side. How would you describe your rate of growth overall?

Umbrella thorn: Deceptively rapid. I have a fixed support structure, but my expendables grow fast to be harvested continually and in large quantities. Not only do I produce leaf after leaf, regardless of whether these are eaten by browsers, but unlike some trees, I tolerate grasses growing under me. So I often have a more literal grazing lawn as my ‘ground floor’. The more browsing and grazing, the faster my production, partly because consumers leave urine and faeces to fertilise me. But a snapshot of me as a woody plant may be too static to reveal my dynamism.

Robin: I have a feeling that many listeners, who are used to thinking of plants as victims of animals, will find it a bit hard to swallow this image of a Good Samaritan. Biologists are trained to sniff out anything faintly anthropocentric or religious. So can we cross-question you from some different angles to make sure we understand you?

Umbrella Thorn: Be my guest.

Robin: Why don’t most trees in well-watered savannas adopt your almost painfully positive attitude?

Umbrella Thorn: Please bear in mind that I grow only on those surfaces that haven’t been depleted of zinc, copper, cobalt, molybdenum, and other nutrients. Over most of my range, this plenitude occurs mainly because there’s so little rain that even coarse soils, lacking in humus, receive nutritious dust that isn’t readily washed away. Where there is enough rain to leach the soil of nutrients, I tend to be restricted to volcanic soils. Unlike more impoverished plants on poorer soils, I can afford to give until it hurts a bit. And anyway in my situation, if I weren’t generous, then inevitably some other competing plant would be.

Robin: That does help to explain your strategy.

Umbrella Thorn: I’ve made a way of life adapting to circumstance rather than feeling victimised. If you run a thought-experiment in which all the animals eating me vanished, I think I would lose my edge and eventually have to give way to less productive plants.

The Honey Badger: Can you give us an example of a coexisting plant that, unlike you, really is miserly?

Umbrella Thorn: Well, how about the myrrhs, which sound holier-than-thou but are thorny in the strict sense. They sulk, bare of leaves, for most of the year, produce a few small flowers and only one seed per dry capsule, and then wrap each seed in its own aril for birds to disperse them with minimum wastage. Even their gum is so antibiotic that, in contrast to acacia gum, it cannot be eaten.

The Honey Badger: What would be your message to the myrrhs of this world?

Umbrella Thorn: Well, they can be as frugal as they like, but I believe in stimulating the economy and the mammals are on my side. The myrrhs usually get relegated to rocky soils where I can’t get the nutrients I need.

The Honey Badger: So, overall, which resources are most indispensible to you?

Umbrella thorn: Natural fertiliser and lots of sunshine. I grow only where the soil is nutrient-rich enough to support large animals in the first place – even if only the camel remains in my Saharan range – and where the animals recycle the nutrients rapidly. Nitrogen-fixing plants like me can be factories for protein, but we need catalysts and energy. My energy-fixing leaves are especially complex and dynamic. They have moving parts despite the fact that they’re small for an acacia tree. My multi-surfaced leaves absorb carbon from the air efficiently and can nimbly track the sun from morning to evening, but in order to save water, my leaflets can also fold closed at night and in drought.

Robin: To fold up this interview, could you state your deal with mammals directly, for the benefit of listeners?

Umbrella thorn: My message is: please eat from my plate as long as you mind your table manners. Call me what you like, a lawn on stilts, a branched buffet. If I give browsers the occasional tongue-lashing, it’s out of my concern to keep feeding you. I invite mammals to plant me and fertilize me with bodily wastes – in this case, not the browsers so much as the grazers. To primates, including humans, I’m sorry I don’t make harvestable gum, but there’s no acacia who makes it up to you in more ways than I. And thanks for pausing under my canopy to listen – and to lighten.

The Honey Badger: Why do you flower in the rainy season? Is it because that’s when pollinating bees[1] are about?

Umbrella Thorn: Actually, I harbour so many different pollen-rubbing insects (see Figure 5) that I would be pollinated even if I flowered in the dry season. And anyway I make far more pollen than is strictly necessary for my reproduction, much of it consumed by various insects. The real reason for my timing is that I want my fruits to ripen at the critical point, so as to fall just when the grass is sparse and brown and the hoofed grazers are leanest.

The Honey Badger: You deliberately cast your fruits before hungry animals?

Umbrella Thorn: Yes, unlike most African acacias and with more dedication than even the other vachellias. And some of the animals I cater to are gracious enough to plant my seeds in suitable open spaces in return. As I said, it’s reciprocal.

Robin: Could you describe your fruits for us? Aren’t they pods as in most other legumes, with cardboard-like walls around a single row of rather hard seeds?

Umbrella Thorn: Yes, they are legume pods, and that means that when ripe they are dry, crisp and hollow, not succulent as in conventional edible fruits. Or even like a green bean[2], which is actually eaten at an immature stage. The difference is that, unlike the pods of most other acacias and indeed most legumes, mine don’t open when mature. Instead, my pods keep some sugar and starch in the fully dry pod-walls; they retain all their loose seeds; and they’re coiled to make the whole pod easy to pick up off the ground without getting too much grit between the teeth, to which ruminants[3] are sensitive. I also do some advertising: my ripe pods are attractive because they’re fragrant and the seeds rattle inside the pods as they fall to the ground. When the impala[4] smells and hears this ‘dinner announcement’, it drops its grazing and runs excitedly over to my tree (see Figure 6).

Acknowledgements:

Our sincere thanks go to David Bygott for permission to use his image of the umbrella thorn silhouette on the front cover. Figures without attribution are in the public domain.

***

All text and images appearing in this blog are subject to copyright, except those images explicitly stated to be in the public domain. You are not free to use any photographs, for any purpose, without receiving written permission from the copyright holder.

[1] The honey bee (Apis mellifera) is native to the habit of umbrella thorn, whereas it is not native to the habitat of several hundred species of acacias in Australasia which have apparently similar flowers and inflorescences.

[2] Fabaceae: Phaseolus vulgaris

[3] Artiodactyla: Ruminantia: Bovidae

[4] Bovidae: Aepyceros melampus